January can be a tough month for year-round gardeners on Nantucket. With a mailbox filled with garden supply and seed catalogues, it can be nearly impossible to stay inside on those random “almost warm” days. Maybe you want to get some of the hard spring clean-up work done early? Thinking about easing off some of those holiday lbs?

If a few warm, dry days are forcast, why not do your mulching? The plants certainly don’t care if you get it out of the way. Trees, shrubs and perennials all benefit from a nice layer of mulch to keep soil temperatures regulated during winter freeze and thaw cycles.

Don’t forget, plants that are suited to growing in the North East naturally create their own mulch. Fallen leaves, needles, ground cover plants and spent growth from previous growing seasons carpet the ground in natural forests and meadows all winter. We tend to tamper with this natural system. A combination of leaf and pine needle cleanup, and high winter wind can really thin down the mulch layer on top of the soil, especially if you are the kind of gardener that likes to keep your beds super-clean. If you do want to do some mulching, here are some tips:

SITE PREP:

It’s best to work in the garden when the soil is on the dry side to avoid compaction. If we have a wet spell, stay out the garden all together.

If you have mulch delivered, or you like to work from a pile in a centralized location, consider layering two tarps on top of each other before dropping the mulch off the truck. Preventing mulch from migrating onto your lawn, or into the gravel or shell in the driveway is the best way to avoid an annoying clean-up after a long day.

Be sure to pull any weeds you find growing before you begin. Some gardeners have the idea that mulch “smothers” weeds. But I guarantee you, mulch spread at the proper depth will not irradicate grass, dandilions, or any other perennial weeds.

If you use organic fertilizer, feel free to apply it before the mulch goes down. Organic fertilizers can be used any time of year, because their nutrients are only available to plants when soil organisms can break them down for plants to use. When temperatures rise in spring, and soil organisms become active, the fertilizer is in place, ready for them to break down and give to your plants.

THE REAL HOW TO:

If you are lucky enough to work off of the back of a dump truck, do so. Whenver the mulch gets too far out of reach, put up the tailgate and raise the bed. The much effortlessly slides back into reach.

Work with a partner! Mulching is hard work – split it up by having one person bring and pile mulch into the beds and another spread the piles into an even 3 inch deep layer.

It can be tough to manoever a wheel barrow in tightly planted beds. Use a bucket to scoop mulch from the wheel barrow and dump it in piles throughout the beds

Small piles of mulch are much easier to spread than large ones. If your partner runs out of mulch in a particular spot you can bring him another bucket-full on the next trip.

Mulch is most easily scooped with a light pitchfork with three or four tines.

If you are working with a few friends, and you want to avoid a lull in work, let everyone make piles, then go to pick up more mulch. Your helpers can spread what is on the ground while you go to get the next load.

AVOID COMMON MISTAKES:

Never let mulch touch the crown of plants. One of the benefits of mulch is that it holds moisture. But this moisture next to the crown of plants can cause more harm than good. This is especially true with trees and shrubs. Leave a space of a few inches around the trunks of trees and the base of shrubs. This will ensure mulch doesn’t rot the bark close to the soil, or make a home for insects like turpentine beetles.

Mulch is at its best when it is spread 3 inches deep; much less and it’s not effective, much more and it is just a waste. Not to mention that thick layers of mulch can build up over time causing numerous problems. Try to be aware of the thickness of the mulch before you start and as you are working. If your garden still has a thin layer of mulch from last year, you may only need to add another inch or two.

Don’t let mulch pile up next to hardwood shingles on your house or outbuildings. The mulch will quickly rot out the lower shingles, forcing you to replace them sooner than you would otherwise.

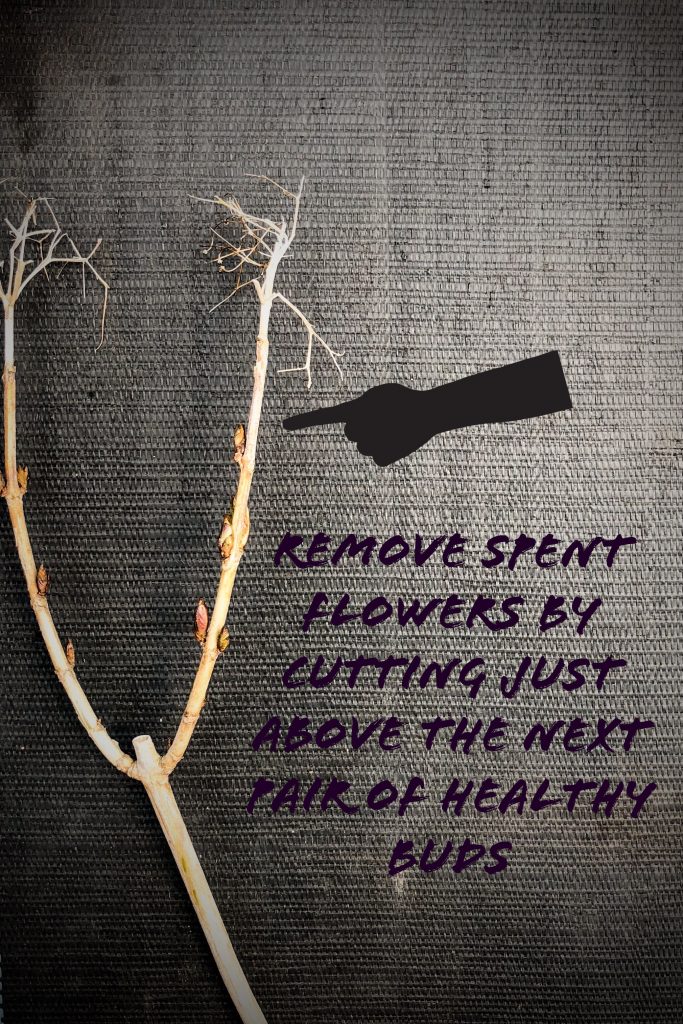

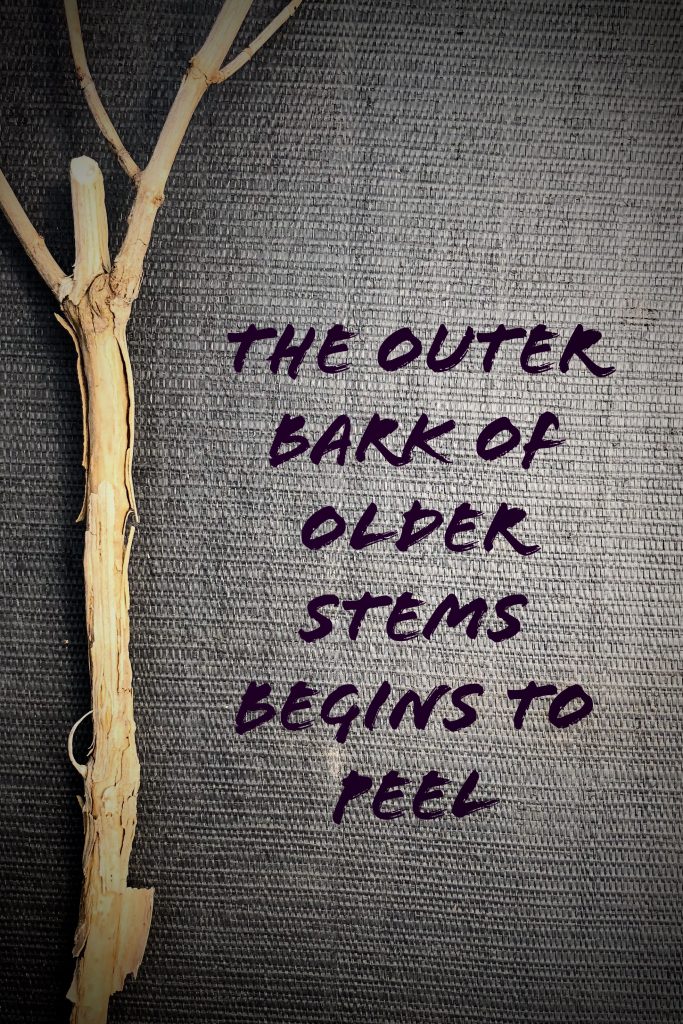

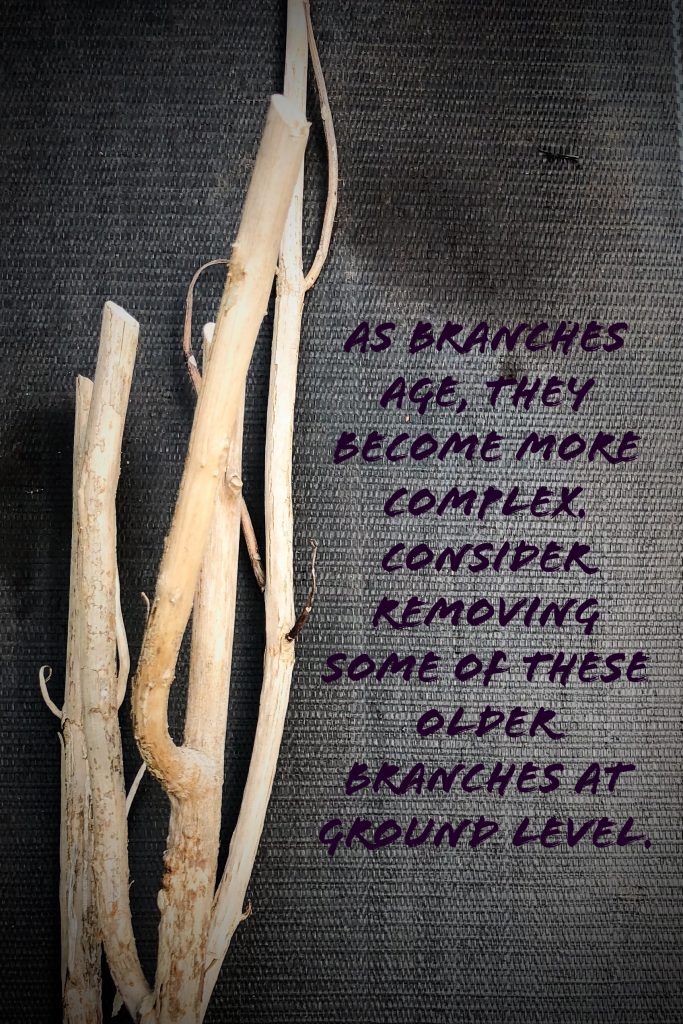

Lady’s Mantle is one of the most common perennials in Nantucket gardens for good reason. These charming plants are incredibly reliable, rabbit and deer resistant and have loads of flower power over a long period. They look spectacular in early summer when the plant is covered in chartreuse-yellow flowers. The tiny star-shaped airy flowers look just as well in a cut flower arrangement as in the garden. When not in flower, the fuzzy

Lady’s Mantle is one of the most common perennials in Nantucket gardens for good reason. These charming plants are incredibly reliable, rabbit and deer resistant and have loads of flower power over a long period. They look spectacular in early summer when the plant is covered in chartreuse-yellow flowers. The tiny star-shaped airy flowers look just as well in a cut flower arrangement as in the garden. When not in flower, the fuzzy